The Papers of Seymore Wainscott: A word from the author

By Al R. Young

In 1959, I accompanied my parents on a trip to Fort Eustis, Virginia, situated on the north shore of the James River not far from George Washington's headquarters at York Town. Like many of our family vacations, Dad combined work with pleasure to help fund the trip, which meant that much of the sightseeing took place around his work, either in the watercolor light of early morning or the soft shadows of late evening; dreamy times of day when the world either stirs to wakefulness or gathers itself to sleep.

This simple circumstance imbued many of the places we visited with a palpable sense of mystery. And in the case of the Capital Mall, its eerie grandeur was greatly enhanced by the fact that we had the greensward avenues, the meandering tree-lined shores, and the silent solemn monuments almost entirely to ourselves. No one had any idea of the profound impression these unplanned conditions were making on the little boy they had in tow—a boy who was experiencing everything with the soul of a poet. Nevertheless, young as he was, or perhaps precisely because he was so young, the impression of the mood was indelible. Even during the day when twilight magic steps back to watch wistfully while life is crammed with all the other stuff—like boredom and school and doctor visits and waiting—I whiled away the timeless hours in the soft breezes and cool shadows of the trees while the tidal waters of the James River glistened in dancing sunlight and mingled with the sea.

Twenty years later, with invitations to study at several graduate schools, that same little boy chose the University of Virginia. Of course, there was far more to such a momentous decision than the memory of that long-ago trip, but excitement surrounding a return to what I felt during that first visit to the colonial cradle of America was undeniably important to me. So, in 1979, as told in The Boxwood Folios Volume One, my wife and I packed up our home and moved cross-country to Charlottesville, Virginia. We thought we were there for me to study documentary editing and colonial American history, and so I did, but, unawares, I also commenced upon one of the longest and most demanding creative projects of my life: The Papers of Seymore Wainscott. In addition to immersion in the setting for the story, my brief exposure to documentary editing under the tutelage of professors like Dorothy Twohig left a lasting impression upon my approach to history. My Father's Captivity, for example (not to mention The BenHaven Archives), is almost as much of a documentary editing project as a narrative history because it presents the home-front portion of the story through letters and other primary sources.

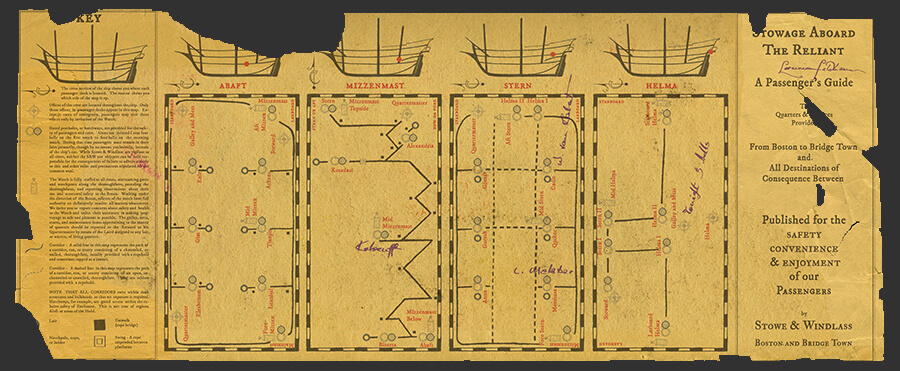

The documentary approach, now referred to as scholarly editing, adds freshness, vitality, and individuality to historical fiction because it facilitates the kind of life and living embedded in original documents and artifacts, such as the unique perspectives and individual voices of characters or the hand oils and scuff marks with which old tools are worn. Being an avid diarist, correspondent, and writer of many things in many formats, I find that documentary editing, as a literary form, offers a most pleasing and rewarding scope for expression, verisimilitude, and complexity. Furthermore, as a graduate student and then in various professional research roles over the years, I have necessarily been engaged by literature in which footnotes are at least as interesting as the text to which they belong. Additionally, the sheer meticulousness involved in preparing the story for publication satisfies all of my inclinations as an editor. Then, being able to lose myself in preparing the occasional document facsimile from the wainscott collection is even more rewarding for the artist in me.

|

| Leornian Feldham's copy of stowage aboard the reliant, a folding pocket map from his 1737 voyage to the Caribee Islands |

Photographs by Alfred R. Young

Tags: 2016

Browse articles by year: 2024 . 2023 . 2022 . 2021 . 2020 . 2019 . 2018 . 2017 . 2016 . 2015 . 2014 . 2013 . 2012 . 2011 . 2010 . 2009 . 2008 . 2007 . 2006 . 2005 . 2004 . 2003 . 2002 . 2001 . 2000 . 1999 . 1998 . 1997 . 1996

Browse articles by topic: Art lessons . BenHaven Archives . Blank art diaries . Fine art photography . Framing . Illustration . Inspiration and creativity . Isles of Rune . Limited Editions Collection . My Fathers Captivity . News . Novellas . Oil paintings and prints . Operations announcements . Orders and shipping . Overview . Portfolios . The Papers of Seymore Wainscott . Project commentaries . Recipes by Nancy Young . Recommended reading . Recommended viewing . Temple artworks . The Storybook Home Journal . Tips and techniques . Tools supplies and operations

Browse articles by topic: Art lessons . BenHaven Archives . Blank art diaries . Fine art photography . Framing . Illustration . Inspiration and creativity . Isles of Rune . Limited Editions Collection . My Fathers Captivity . News . Novellas . Oil paintings and prints . Operations announcements . Orders and shipping . Overview . Portfolios . The Papers of Seymore Wainscott . Project commentaries . Recipes by Nancy Young . Recommended reading . Recommended viewing . Temple artworks . The Storybook Home Journal . Tips and techniques . Tools supplies and operations